Belize welcomes and actively pursues foreign investment, but high costs associated with doing business, bureaucratic delays, and corruption present substantial obstacles.

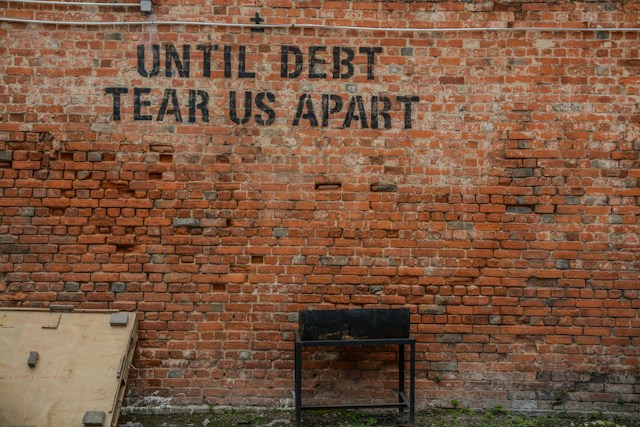

In 2020, The Nature Conservancy (“TNC”) assisted Belize in restructuring its debt by purchasing back Eurobonds at a substantial discount and investing the savings into marine conservation efforts. This innovative “debt-for-nature” swap represents an innovative model for combatting climate change and poverty simultaneously.

Sources of Debt

Belize’s external debt is mostly held by private sector investors; most bonds held by foreigners. But the country has been reluctant to incur additional debt, perhaps due to lack of financial markets and investor interest or due to poor rankings on international surveys measuring ease of doing business and corruption.

Belize is a member of CARICOM, which assists it with coordinating its foreign, economic and trade policies with other members. Belize also participates in the OECD Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting but its foreign policy tends to be determined regionally; tariffs in Belize are determined primarily based on CARICOM’s Common External Tariff, while several free trade agreements such as GSP and Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act exist between it and Belize.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, the government was faced with its most severe economic and fiscal crisis ever, including massive levels of debt and the immediate need to address critical social issues such as their effect on poor households. To combat this crisis, they enacted a debt-for-nature swap agreement with TNC and its affiliates to help lower outstanding national debt levels.

TNC subsidiary Lending Belize money at a discount to purchase its pricey “Superbond”, then replacing that money with “blue bonds”, financing investments in marine ecosystems. This strategy allowed TNC to pass along unattractive Superbond debt while raising money for conservation initiatives.

TNC and Credit Suisse had to persuade investors to assume the risks involved with investing in Belize’s blue bonds for it to work; this wasn’t easy since many investors were skeptical of Belize’s government being able to pay its debt back, doubted its sustainability, and were wary about lending money to a nation which has experienced high levels of corruption in recent years.

After extensive discussions and negotiations, several major financial institutions and sovereign wealth funds agreed to invest in blue bonds – creating a successful debt-for-nature swap that saved Belize’s credit rating, enhanced its capacity to service remaining debt, and provided capital towards marine conservation efforts.

Repayment Terms

The debt for marine conservation swap was one of the most complex sovereign bond transactions ever undertaken and only achieved its success through enormous team effort from all stakeholders involved – such as Belizean sovereign, creditors, TNC, DFC and Credits Suisse. For its success to occur smoothly through conditionality. Furthermore, to make it all come together successfully it was vital that both legal advisors and financial advisors drew on prior experience from previous bond restructurings and marine conservation finance deals to devise an optimal transaction structure for Belize.

TNC extended funds to Belize through a special purpose vehicle incorporated in the U.S. (the “Blue Loan”) backed by their sovereign BBIC bonds; TNC then purchased out Belize’s Eurobonds at approximately 55 cents on the dollar, significantly decreasing their external commercial debt by 9 percentage points of GDP.

Belize was required by its Blue Loan to take additional measures for coastal and marine conservation in addition to debt restructuring, including increasing biodiversity protection zones to 30 percent of ocean area by 2026, working with TNC and other stakeholders on an ecosystem management plan, and creating a conservation trust. Part of its fiscal savings from debt restructuring were dedicated towards funding this new commitment from government.

Belize has enjoyed peaceful, transparent, democratic elections since independence on September 21, 1981. The political environment of the country features two major parties competing for power in each election cycle and often changing leadership once elected to office. Belize’s economy is driven by services industries which employ nearly half the workforce while contributing nearly one quarter to GDP.

Belize provides an inviting investment environment, without laws or policies that discriminate against foreign investors. However, some barriers exist for investment such as unreliable land titles and lengthy bureaucratic processes for licensing businesses. Furthermore, few specialized courts exist to resolve investment disputes; most disputes between Belizean firms and U.S. firms have typically been settled through international arbitration panels.

Impact on the Economy

Belize’s relatively high per capita GDP, political and currency stability, bilingual population, developing infrastructure and export diversification have attracted foreign direct investment (FDI). Belize encourages FDI in sectors like tourism, business processing outsourcing, telecoms, agriculture and renewable energy – to relieve fiscal pressure and diversify their economy; however, with such challenges as high costs of doing business, corruption and bureaucratic delays impeding potential investment flows into these sectors.

In 2021, the government revamped its tax system by consolidating offices for personal income taxes and corporate income taxes into one agency with an online payment system for both personal and corporate income taxes. They also digitalized Companies Registries and courts to speed up registration/filing documents as well as payment of fees faster.

In March 2022, the government introduced new business tax cuts designed to encourage lending by banks and financial institutions in strategic foreign exchange earning sectors while simultaneously raising taxes in specific industries to disincentivize personal and distribution loans – with this expected to improve revenue collection while decreasing leakage.

Government efforts also centered around strengthening legal and institutional frameworks to bolster investor protection. Belize’s Constitution and Civil Code include three international conventions into domestic law: 1923 Geneva Protocol on Arbitration Clauses; Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards; and New York Convention. Furthermore, they ratified the Convention on Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals from Other Countries.

Belize’s climate change strategy reflects its status as a small island developing state vulnerable to climate changes. Belize has pledged to pursue a low carbon development path through a National Determined Contributions (NDC) roadmap aligned with global goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Belize faces considerable environmental constraints and risks associated with natural disasters, requiring significant investments to reduce vulnerability through investments in a coastal resilience plan. Furthermore, efforts are underway to increase clean energy sources with renewable energy strategy investments; while an ambitious waste management program aimed at a 50% decrease in municipal solid waste by 2024 has also been put in place.

Conclusions

Belize’s external debt, consisting of foreign loans and grants from creditors outside the country, accounted for 61.2% of GDP as of 2021 – higher than Central America and Caribbean average of 49.5%. According to World Bank Doing Business Report for 2020, Belize ranked 135 out of 190 economies for ease of doing business, experiencing difficulties such as depth of credit information availability; lack of a credit bureau/collateral registry; and time consuming and costly insolvency procedures.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) joined with Belize Government officials to launch a debt-for-nature swap, effectively turning some of their debt into conservation investments. To buy out existing bondholders, TNC created the Belize Blue Investment Company (“BBIC”) as an investor-friendly special purpose entity located in Delaware – borrowing money from Credit Suisse Group AG with non-recourse loan terms so it may only take legal action against its assets but not against Belize itself – in return entering into an environmental conservation agreement between BBIC, Belize Government officials and local stakeholders.

Belize was not alone in using debt-for-nature agreements to finance climate and conservation projects; many other nations have utilized similar deals; but Belize’s was both prominent and complex. Success of this deal demonstrates the viability of similar investments for small and medium-sized economies with high debt-to-GDP ratios. This landmark deal, the largest blue bond for conservation to date and secured with $610 million of political risk insurance from Development Finance Corporation and Credit Suisse Group, required meticulous and timely public consent solicitation, bond tendering and negotiation processes. Both conservation agreement and Blue Loan include cross-default clauses which encourage Belize to uphold their obligations.

Belize is generally welcoming of foreign investment and does not impose restrictions on establishing private businesses. Furthermore, its constitution and legislation ensure property rights for individuals regardless of nationality; and Belizean courts such as the Supreme Court supervise dispute settlement between private parties through arbitration processes; foreign arbitral awards against the government are usually recognized although they may be challenged through appeal to the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ).